Rec Room #3: Post-Commie Central Europe Books, of Course!

Whiskey robbers, Stasi files, NATO pre-revisionism, and pet rodents named Václav.

Listen, as long as the other two Ringo-seals are too busy fighting code-inspectors in East Egg and/or helicoptering to the Neverending Conference, I’ll keep filling up this here real estate with more belated answers to your book-recommendation queries. Which, given certain monomanias, tend to cluster around a theme, or at least a geographical region. But first! A word from our sponsors (which is us):

This query, from listener Matt, dating from March 2021, reads, in part:

[W]ould love to hear any other book recs you guys have on post-Communist Eastern/Central Europe. I’m always blown away by the knowledge you guys have and love getting to hear you flex it.

This other Matt will be issuing apologies, though certainly not refunds, over in the comments.

So first, a story (*ducks*): It was sometime in 1994, and I was hanging out in circles more rarified than would normally befit a hippie scumbag 26-year-old part-time street musician. My galpal at the time, a returned émigré 10 years my senior, worked for Václav Havel’s office in the Prague castle, and would occasionally let me sit at the grownups’ table. It was one of those dinner parties that has a Topic of Conversation (a practice that still makes me wince another lifetime later), so to this assemblage of all-older-than-me international diplomats, journalists, and thinkers was posed: When, exactly, did it all start to go so terribly wrong?

The “it” was that post-Velvet Revolution spirit of exuberance and promise and discovery, not just in the then-Czechoslovakia (whose dissolution at the beginning of 1993 was seen as one of the key wrong turns), but also the post-communist region as a whole, which back then was being particularly traumatized by the ongoing slaughter in Bosnia. Did the worm begin turning when nationalist Slovaks in Bratislava threw eggs at a visiting Havel in October 1991? When Slovenia seceded from Yugoslavia four months earlier? Or did the infamous Pink Tank episode and aftermath in April and May 1991 mark the beginning of the end?

Ears slowly reddening, I tried very hard not to talk. Having forged lifetime friendships with kids who at a critical point in their lives between ages 18-22 risked everything to fight (and defeat!) communism without firing a shot, I suggested very slowly and quietly when finally summoned that I didn’t think this particular generation considered life to be worse in 1994 than it had been in 1991, to say nothing of 1988. Stores were still called “store” in 1991, and had very little in them; now you could go hog-wild in a hypermarket. Movie theaters three years prior routinely featured babičkas with microphones live-dubbing all the lines of whatever dated straight-to-video Andy Garcia thriller they could scrounge; now we were watching pristine versions of Pulp Fiction and True Lies during opening month or even week. Czechs could now travel—not just legally, but financially. And Prague, much more then than in 1991, had reasserted itself as the both the literal and cultural capitol of Bohemia.

It may just be, I suggested as delicately as I could, that journalists, academics and diplomats who did absolutely heroic, crucial work bolstering the anti-communist cause in the 1980s were not exactly in the best place to assess the wide-open ‘90s.

To my utter shock, I was not expelled from the conversation, but rather buttressed by a chap from Radio Free Europe, who said something to the effect of, Yeah, we got used to the bad old way of life that we despised; or at least understood our own place in it & how everything worked, and now maybe we’re just too out of touch to understand the kidz. I thought, then and now, that this was a remarkably magnanimous and healthily self-critical way to go about the internal business of being (to use a Central Europe phrase I have always resisted) a public intellectual.

The moral of the story isn’t that I was right then—though I pretty much was—but that I’m wrong now. Or at least, I’m the RFE guy, recognizing my limitations and the distortions created by being anchored in 1990-97. So take the ensuing recommendations with those grains of salt.

The first thing to say in any list of post-commie Central European books is that I haven’t read most of them, including three of the most famous: Arthur Phillips’ 2002 Prague: A Novel, which was not about Prague but about expatriate Budapest, complete with various noms-de-people-I-know; Michael Žantovský’s 2014 Havel: A Life (I’m getting to it, I’m getting to it!); and Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2002 Everything Is Illuminated, though I did see and greatly enjoy the 2005 movie, starring Elijah Wood (and also the dude from Gogol Bordello) as a youngish American Jew who wanders around post-Soviet Ukraine looking for the woman who saved his grandfather’s life in the Holocaust. There were very familiar notes in that movie, and I presume the book, about the often absurd, often semi-tragic mutual incomprehensions that ensued when ignorant westerners came poking behind what had been just a huge black nothingness on the map, bringing God knows whatever else hangups on their own.

Throat finally cleared, here’s a list of post-communist Mitteleuropean books, presented roughly in the order that I think the #Fifdom will enjoy:

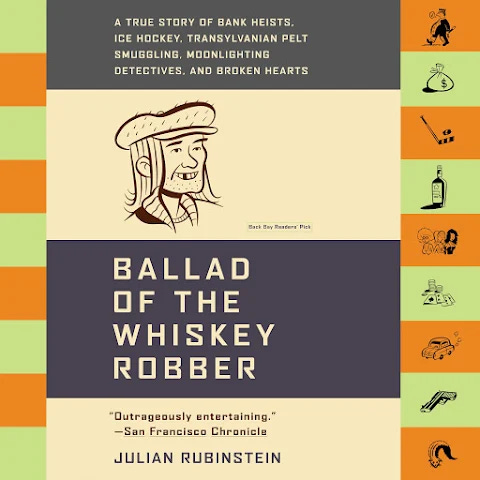

1) Ballad of the Whiskey Robber: A True Story of Bank Heists, Ice Hockey, Transylvanian Pelt Smuggling, Moonlighting Detectives, and Broken Hearts, by Julian Rubinstein (2004). I mean, if you’re not sold by the title/subtitle, I don’t know what to tell you.

No really, this one’s at or near the very top of the list of Books You’ve Never Heard of That Matt Knows You Will Like. (Warren Hinckle’s If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade: An Essential Memoir of a Lunatic Decade is another on the shortlist.) The thing just hurtles hilariously downhill from the opening prison break of post-communism’s most celebrated (and handsome) bank robber, whose string of crimes coincided with my time there. It is not for even one moment necessary to have any useful knowledge about late-‘90s Budapest to enjoy this romp, but Rubinstein deserves extra credit for accurately capturing the sights and smells and conflicts of time and place. I see there was a 2017 Hungarian movie made of this, and…the trailer certainly does not capture the hectic/arch tone of the source material:

2) The File: A Personal History, by Timothy Garton Ash (1997). I have certainly mentioned this one on a podcast or two.

Garton Ash, an Oxford “historian of the present” (in his apt words) is the foremost chronicler of modern Central Europe, most famous for his 1990 book, The Magic Lantern: The Revolution of '89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin and Prague. I will recommend another one of his post-commie books below; you could fill a whole list of his various door-stoppers about Germany and so forth. But this one by far is my favorite to read and the least consequential, dealing as it does with the unlocked Stasi files on a comparatively unimportant visiting British graduate student in 1978 Berlin named…Timothy Garton Ash.

This ultimately becomes a perfect companion piece to The Lives of Others (a movie that if you haven’t seen it, close out of this right now & fix it); as well as Anna Funder’s Stasiland. Garton Ash obtains his file, compares it to his own cringeworthy diary of the time, and then goes and reinterviews the people (including intimates) who informed on him. Yes, it’s a fascinating slice of totalitarianism—why and how and to what extent do people collaborate with the police state, and how do they justify it to themselves two decades later?—but what lingers are the poignant results of a middle-aged public intellectual (that term!) going back and re-reporting his own memory, his own previous self:

The diary reminds me of all the fumblings, the clumsiness, the pretentiousness and snobbery—and the insouciance with which I barged into other people’s lives. Embarrassment apart, there is the sheer difficulty of reconstructing how you really thought and felt. How much easier to do it to other people! At times, this past self is such a stranger to me that where I have written “I” in these last pages I almost feel it should be “he.”

3) Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, by Tony Judt (2005). A key source text of my recent Reason cover essay, “After the War: In the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, it's time for Europe to step up and America to step back.”

The post-commie section is only Part Four of a four-part book, and by far the least important, and yet I would argue that this magisterial account of post-World War II reconstruction and political/social developments, which was conceived of as an idea in December 1989 as a direct response to communism being in mid-collapse, is an essential and humane (if pitiless) understanding about the birth, life, death, and afterlife of the Cold War. Truly a must-read, though a bit of a honker.

4) The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism, by Tina Rosenberg (1995). In the same vein as The File; won a National Book Award and a Pulitzer.

Haunted Land is a well-reported, complexity-embracing examination of how post-communist countries addressed (and sometimes ignored) the legal, political, and moral reconciliations required by such a neck-snappingly fast changeover from totalitarianism to liberal democracy. What do you do with the secret police files, and the names of supposed collaborators that show up on them? How do you reallocate property seized from private owners by a no-longer totalizing state, and where do you draw those particular statutes of limitations? Who gets charged with the murder of the last souls cut down while attempting to escape East Germany? And what happens when former dictators become friends with the dissidents they imprisoned?

On some level, every country in the region had to deal with these issues, and in the future those currently trapped in various authoritarian hellholes will be asking the same types of questions. If nothing else, Haunted Land should disabuse critics from passing too hasty a judgment on the choices captive peoples make in circumstances we are fortunate to never encounter.

5) Rock ‘n’ Roll: A New Play, by Tom Stoppard (production premiered in 2006). You ever see a playwright do a subject you’ve written 30,000-plus words about, and just kick you all sorts of sideways? That’s what it felt like seeing Rock ‘n’ Roll in Washington, D.C., 13 years ago. And I remain so very grateful for it.

Stoppard, the celebrated Czech-born British playwright and screenwriter whose Jewish family fled the Nazis in 1939 when he was 20 months old and who worked closely during communism with the dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, produced here the definitive if fictionally rendered account of how, as if by alchemy, The Velvet Underground and Nico found its way into 1968 Prague, enchanted a group of musical dirtbags called The Plastic People of the Universe, whose repression by the post-Warsaw Pact invasion Communist government eventually led to Havel and comrades launching Charter 77, which eventually helped topple the whole superstructure of international communism.

Better yet, Stoppard did so while presenting a through-the-decades complicated relationship between a true-believing Cambridge commie professor and an actual Czech/anti-communist student, with all kinds of finely observed empathy for the fallibility and skewered viewpoints of people coping with a world not free. It’s so good, people! Here’s a representative trailer from one production:

6) Opening NATO’s Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era, by Ronald D. Asmus (2002). OK, this is for the hardcore set. But while it’s a Council of Foreign Relations production (hissss!!!!), and was the first rather than the last book-length account of NATO expansion, it is a very useful account to have in your brain-holster when some faux-sophisticate tries to tell you what was REALLY driving the new growth of the old group. (Hint: It wasn’t primarily about America.)

Asmus was part of that process, so yes, this is an America-centric, pro-expansionist view. But I can tell you from having covered and observed a whole helluva lot of related material in the early 1990s, the account is true wherever it overlaps with my knowledge. Whether that activity was wise is a completely separate question.

7) History of the Present: Essays, Sketches, and Dispatches from Europe in the 1990s, by Timothy Garton Ash (2000). Look, the assignment was post-communism, and if you want to know about what that first decade was like (albeit from the higher-echelon points of view), this is a fine collection.

8) Necessary Errors, by Caleb Crain (2013). I saved the least for last, in terms of weight, but that’s no ding on an American-in-Prague novel by a neighbor of mine who so captured a time and place and viewpoint I lived through that I began to doubt where my reality ended and his fiction began. From my Wall Street Journal review (commissioned, as the editor himself recently reminded me, by none other than Sohrab Ahmari!),

[The protagonist] Jacob arrives in August 1990. He occasionally takes baths by pouring successive pots of boiling water into his tub due to a lack of available hot water; hangs out with his expat friends at their favorite pub, U Medvídků; is shocked by the harsh right-wing sentiment among journalists at the revolutionary student newspaper; has someone at the Press Jazz Club accuse him of not knowing anything about jazz; attends a soon-to-be-famous art happening in the bunker underneath a torn-down monument to Joseph Stalin; is ambivalent about the propriety of the Gulf War; hides himself in a bathroom after vomiting sickly sweet Bohemia Sekt at a nightclub; and at some point lives with a pet rodent named Václav. Each and every one of those words, as it turns out, applies accurately to my own time in Prague. (Though in fairness, our Václav was a rat, not a guinea pig.)

Reading other people's descriptions of topics you know intimately is usually a recipe for disillusionment; here, it's almost cause for alarm. "Necessary Errors" so completely recaptures the smells and scenes and political conversations and above all the feelings of 1990-91 Czechoslovakia that I began to actively worry that Mr. Crain was inserting new memories into my brain, now fuzzed up by advancing age and beer residue.

Eight recommendations is enough, yeah?

More podcast content soon!

For those who listen to books more than read them, the version of the Ballad of the Whiskey Robber on Audible is performed by an ensemble cast including Eric Bogosian, Dmitri Martin, and Tommy Ramone.

Why hasn't Matt mentioned he lived in Central Europe on the pod before?